City Know-hows

Target audience

For the attention of: City officials, urban leaders and communities concerned with urban health inequities.

The problem

Residential segregation has been proposed as part of the causal path of different health outcomes, however, it has been studied mostly linked to race in a USA context. It has been proposed that there are five theoretical dimensions of residential segregation, and it was confirmed using indices constructed from race proportions. These indices are widely used, however, in Latin America segregation is mostly determined by socioeconomic and educational levels, not by race.

What we did and why

We aimed to evaluate whether the dimensions are maintained when using the educational level instead of race as segregation variable and the Chilean population instead of USA. We worked with census data for the proportion of the population of 25 years or older that have completed university education and replicated the methodology used to determine those five traditional dimensions.

Our study’s contribution

We found that it was not possible to verify the same five dimensions observed in USA from race using the Chilean educational census data. Our study demonstrates the need to locally characterize not only the indices of residential segregation but the theoretical dimensions to which they refer.

Impacts for city policy and practice

There is a need to note that historical and cultural differences between Latin America and USA may translate into different forms of segregation. This means that city/urban policy and practice need to consider that a better characterization of the metrics and dimensions of inequity will improve the interpretations of the effects of segregation on health

Further information

Full research article:

Evaluation of the traditional dimensions of residential segregation by educational level in Chile by Sandra Flores-Alvarado (@sfloresa87), Tamara Doberti Herrera & Mauricio Fuentes-Alburquenque.

Related posts

This study contributes to the broader discourse on urban design for children, offering insights into how cities can create more inclusive, engaging, and health-promoting environments. It supports and adds to existing literature, finding that the alignment of play initiatives with public health goals, and strong collaboration between local government departments are effective in supporting children’s play on the strategic level. It identifies barriers to play in policy, namely budget constraints and deprioritisation of play.

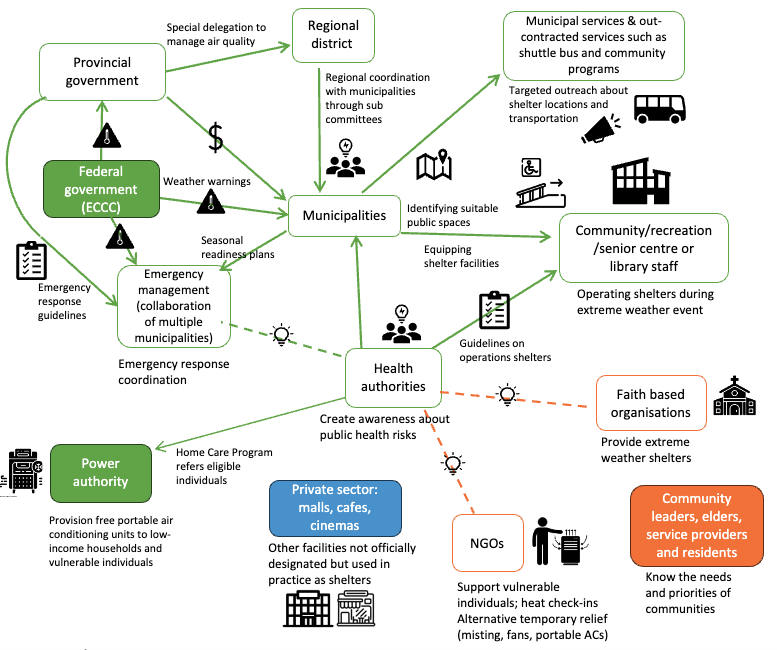

Extreme heat and wildfire smoke are a growing concern in cities. Cooling and cleaner air centres can provide a much-needed respite but too often they’re set up reactively and inconsistently. Our study explores what works, what doesn’t, and how cities can design these spaces to be reliable, inclusive, and accessible for all.

Are you prepared for the health risks of extreme heat? Our new study shows that exposure to extreme heat increases the risk of mortality from Non-Communicable Diseases. Check out our systematic review of the effects of extreme heat, both indoors and outdoors, on health in the UK.